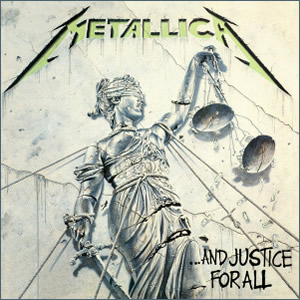

…And Justice for All by Metallica

Buy …And Justice for All Metallica brought their fusion of progressive thrash metal into the mainstream with the double LP …And Justice for All in 1988. The album was nominated for a Grammy […]

Buy …And Justice for All Metallica brought their fusion of progressive thrash metal into the mainstream with the double LP …And Justice for All in 1988. The album was nominated for a Grammy […]

Buy ‘Til the Medicine Takes The 1999 release of ‘Til the Medicine Takes was Widespread Panic‘s sixth studio album and it finely displays the musical breadth of this Athens, Georgia based Southern rock/jam […]