The Doors 1967 Albums

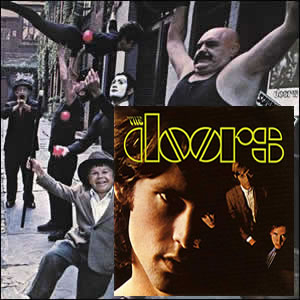

Buy The Doors Buy Strange Days I have been a fan of The Doors music since I was about 12 or 13 and have constantly gone back and forth over which is their […]

Buy The Doors Buy Strange Days I have been a fan of The Doors music since I was about 12 or 13 and have constantly gone back and forth over which is their […]

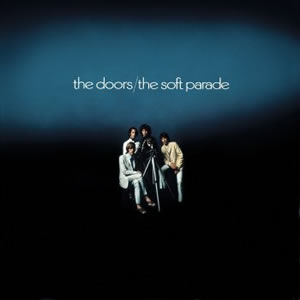

Buy The Soft Parade 1969 was a tumultuous year for the The Doors. The main incident which caused their collective headache happened in Miami in March when vocalist Jim Morrison was arrested for […]

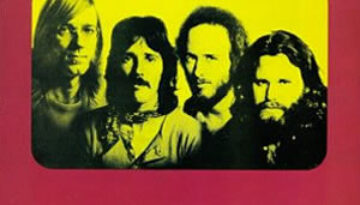

Buy L.A. Woman L.A. Woman, is the final Doors album with lead singer and poet, Jim Morrison. This album encompasses a mixture of blues, funk, and rock while maintaining a sound that is […]