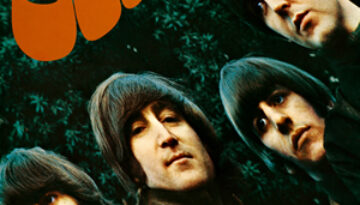

Rubber Soul by The Beatles

Buy Rubber Soul As the years have gone by, Rubber Soul has distinguished itself more and more from the “typical” early album by The Beatles. While the 14 selections remain pretty much bright […]

Buy Rubber Soul As the years have gone by, Rubber Soul has distinguished itself more and more from the “typical” early album by The Beatles. While the 14 selections remain pretty much bright […]

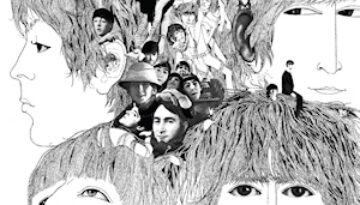

Buy Revolver As many times as I’ve heard someone say they love The Beatles, I have heard someone else say they think they are overrated. To a generation of listeners raised in the […]

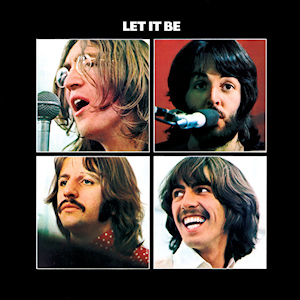

Buy Let It Be Released less than a month after the announcement of their breakup, Let It Be was a unique release by The Beatles on several fronts. First, the bulk of the […]

Buy Help! Their fifth overall studio album, Help!, is perhaps the final of The Beatles‘ pop-centric, “mop-top” era records released over the course of 30 months. Still, the group did make some musical […]

Buy Abbey Road Short of careers cut short by tragedy, there are very few times in rock history where a band or artist finished with their greatest work. Abbey Road, the eleventh and […]