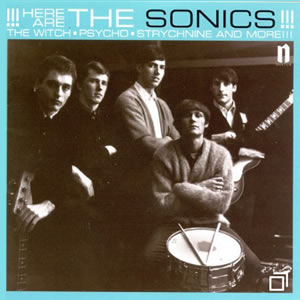

Here Are the Sonics!!!

Buy Here Are the Sonics!!! Here Are The Sonics!!! is the 1965 debut album by American garage rock band The Sonics. The record features a dozen songs of the days’ most powerful and […]

Buy Here Are the Sonics!!! Here Are The Sonics!!! is the 1965 debut album by American garage rock band The Sonics. The record features a dozen songs of the days’ most powerful and […]

Buy Help! Their fifth overall studio album, Help!, is perhaps the final of The Beatles‘ pop-centric, “mop-top” era records released over the course of 30 months. Still, the group did make some musical […]

Buy Having a Rave Up with The Yardbirds Having a Rave Up with The Yardbirds is an oddly constructed mish-mash of recent singles, new recordings, and live tracks recorded over 19 months prior […]

Buy For Your Love About four years ago, we reviewed the 1966 album by The Yardbirds commonly known as “Roger the Engineer”, which saw the final days in the band for guitarist Jeff Beck. […]

Buy Do You Believe in Magic? The Lovin Spoonful had a meteoric career which climaxed shortly after it began in the mid 1960s. Do You Believe in Magic is the 1965 debut album […]

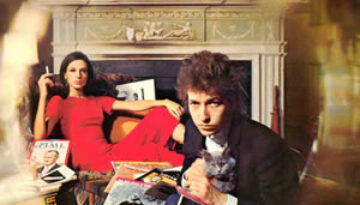

Buy Bringing It All Back Home Perhaps the most lyrically potent album ever, Bob Dylan delivered a masterpiece with his fifth overall album, Bringing It All Back Home, released 50 years ago today […]

Buy Begin Here We commence our year-long celebration of the 50th anniversary of 1965 album releases with the oldest music we’ll ever cover at Classic Rock Review. The British group, The Zombies, recorded […]

Buy Animal Tracks (US version) In 1965, The Animals released a pair of albums that were each titled Animal Tracks, a May 1965 release in their native UK and a September release in […]