The Movie Soundtrack

The movie soundtrack has become a great source for discovering music. Many dramatic scenes are fully augmented by appropriate audio, which in turn drives sales of the songs themselves. It is a nice […]

The movie soundtrack has become a great source for discovering music. Many dramatic scenes are fully augmented by appropriate audio, which in turn drives sales of the songs themselves. It is a nice […]

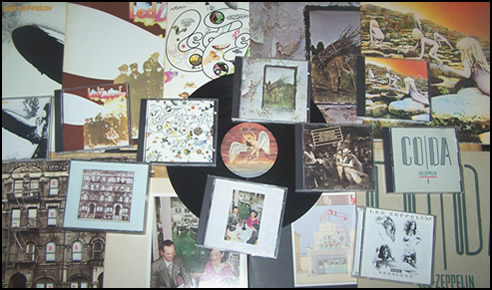

We pretty much cover studio albums exclusively at Classic Rock Review and will continue to do so with the exception of the few studio/live hybrids that we explore later in this article. […]

I recently read an article by NPR intern Emily White in which the 21-year-old pretty much bragged that, despite possessing thousands of songs, she has never really purchased music. In David Clowery’s response […]

Classic Rock Review is built around the concept of the “album”, which we define as a collection of professionally recorded songs by a single artist published together usually through a single source of […]