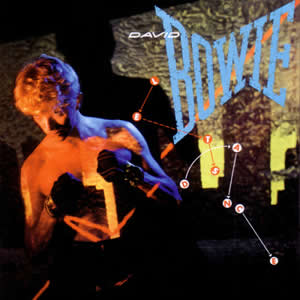

Let’s Dance by David Bowie

Buy Let’s Dance An artist who seemed to constantly reinvent himself, David Bowie created a stylized and soulful new-wave album with a romantic signature on the 1983 album Let’s Dance. It was Bowie’s […]

Buy Let’s Dance An artist who seemed to constantly reinvent himself, David Bowie created a stylized and soulful new-wave album with a romantic signature on the 1983 album Let’s Dance. It was Bowie’s […]

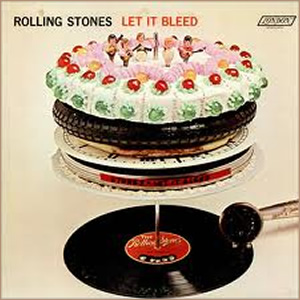

Buy Let It Bleed The middle release of the three greatest Rolling Stones albums, Let It Bleed finished the decade of the 1960s with a mostly solid blues/rock effort which contains a pop/rock […]

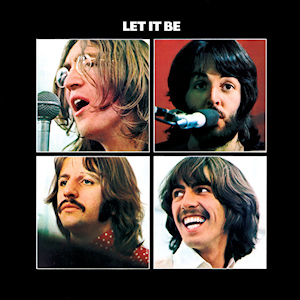

Buy Let It Be Released less than a month after the announcement of their breakup, Let It Be was a unique release by The Beatles on several fronts. First, the bulk of the […]

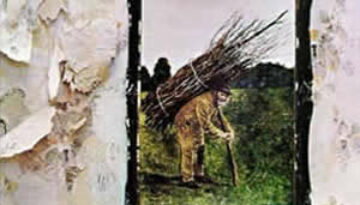

Buy Led Zeppelin IV Led Zeppelin‘s fourth studio album, which has no proper title but is commonly referred to as Led Zeppelin IV, may well be the pinnacle of the band’s early sound. […]

Buy Learning to Crawl Following a very tumultuous period where two band members lost their lives due to drug overdoses, Learning to Crawl, was a bit of an early career comeback album for […]

Buy Layla & Other Assorted Love Songs Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs was the sole studio album by super group Derek & the Dominos. A double length LP, the fourteen tracks on […]

Buy Kinda Kinks The Kinks sophomore effort is often overlooked in their catalog due to the popularity of their recently released debut and the critical acclaim of later albums. But the rapidly recorded […]

Buy Journeyman The 1980s seemed to have been a time for old time rockers to make incredible (albeit short) comebacks after several years in the wilderness. This was case with Paul Simon’s Graceland, […]

Buy John Barleycorn Must Die Traffic returned from a short hiatus with the 1970 album John Barleycorn Must Die. Reformed as a trio, the group built this album mainly on extended, jazz-infused jams […]

A Rock Opera Before it was a theatre act, Broadway play, or motion picture, Jesus Christ Superstar was simply a 1970 rock album produced by composer Andrew Lloyd Webber and lyricist by Tim […]